By William F Hederman, Life Member

Among the giants of early electric power was a man who stood 4 feet tall. Charles Proteus Steinmetz was an immigrant to the United States (U.S.) from Germany. He was almost denied admission to America at Ellis Island in 1889 because of his frail appearance and concern about his capability to find gainful employment. Fortunately for Steinmetz and his adopted country, Steinmetz successfully got through immigration.

EARLY LIFE

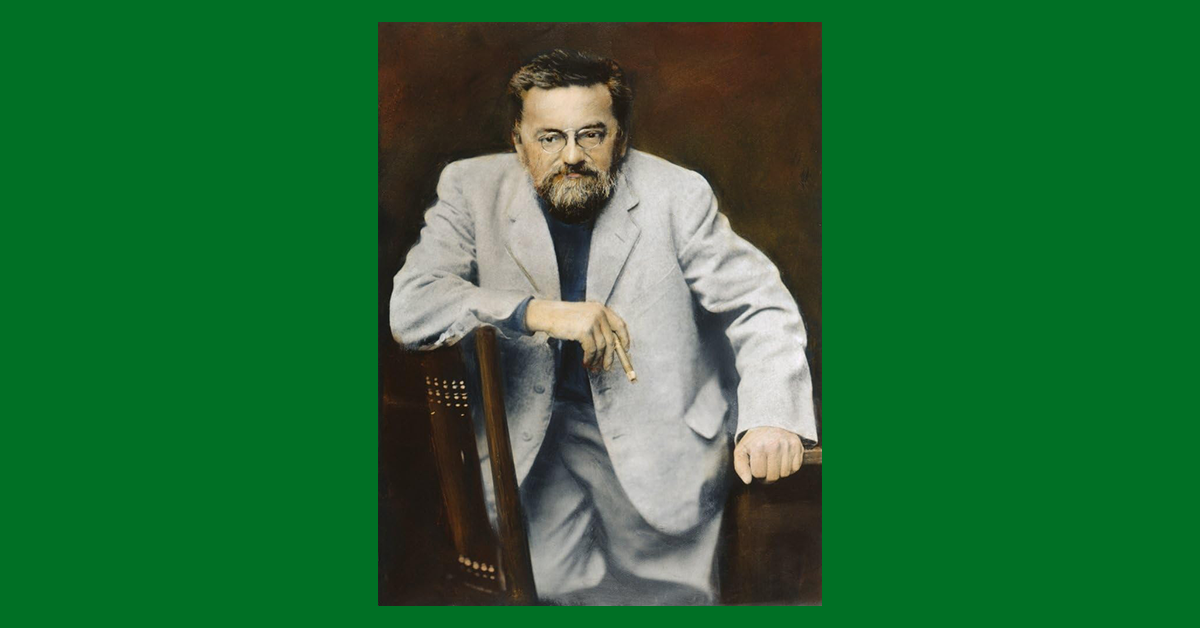

Karl August Rudolph Steinmetz was born on April 9, 1865, in Breslau, Prussia/Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland). His mother died soon after his birth, and he was raised by his stern father and grandmother. He suffered from a hereditary malady, kyphosis, that contorted his body. Both his father and grandfather had the same condition. The condition affected Steinmetz’s self-image, and his self-awareness strengthened his character. He could even join in good-natured teasing about his appearance. The name he chose when applying for U.S. citizenship was Charles Proteus Steinmetz.”Charles” Americanized his Germanic first name, Karl. “Proteus” was a nickname he gained at the University of Breslau, where he earned degrees in 1888. Proteus was a Greek mythological figure who prophesied events and took on strange shapes, always returning to a human hunchback. Steinmetz appreciated the comparison, and he adopted the nickname. This was an important reflection of his pleasant and humane personality.

His move to the U.S. was not entirely his “original dream.” Bismarck’s German government was after him for his activities as a member of the Socialist Student Association at the university. These activities included writing a particularly radical opinion piece in a Socialist publication. In 1889, he left his homeland to avoid arrest and went to Zurich, Switzerland, to the Federal Technology University. When his Swiss visa to study there was close to expiring, Steinmetz decided to accompany a friend to New York.

EARLY CAREER

Through pre-arranged introductions, Steinmetz joined the electrical engineering company Osterheld and Eickmeyer in Yonkers, NY. They were active in building electric motors and were expanding into the electric streetcar business. Eickmeyer was from the same region as Steinmetz, and he quickly came to put great trust in Steinmetz and his technical skills, creating a laboratory that Steinmetz ran.

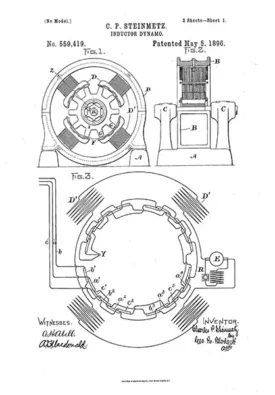

By 1892, Steinmetz had completed important, groundbreaking work regarding energy losses from magnetic hysteresis effects in alternating current equipment. He published his results in Electrical Engineering magazine (“Complex Quantities and their use in Electrical Engineering.”) and presented them to the American Institute of Electrical Engineering (forerunner of the IEEE) in New York in 1892. Steinmetz was particularly effective at applying mathematical concepts (especially complex numbers) to simplify calculations for A/C electrical power solutions. His presentations brought wide and favorable attention to Steinmetz and his employers from the small but influential electrical engineering community in and around New York City. His results were described as transforming A/C problems that had required challenging calculus solutions into problems that could be addressed with algebra.

In 1893, Thomas Edison’s newly formed General Electric Company acquired Steinmetz’s employer, Ostheld and Eickmeyer, when Steinmetz refused to be hired away from his employer.

ENGINEERING SUCCESS

At General Electric, Steinmetz’s first assignment was at the GE plant in Lynn, Massachusetts. There, he led the Calculations Group. Next, he moved to the major GE facility in Schenectady, NY. GE used his gifts to advance practical solutions for challenging problems. Steinmetz focused on three major areas:

At General Electric, Steinmetz’s first assignment was at the GE plant in Lynn, Massachusetts. There, he led the Calculations Group. Next, he moved to the major GE facility in Schenectady, NY. GE used his gifts to advance practical solutions for challenging problems. Steinmetz focused on three major areas:

- Alternating current energy losses through magnetic hysteresis.

- Three-phase alternating power systems

- Transient power system effects, including exploring the effects of lightning (explored by creating man-made lightning).

In 1910, Edison, on advice from Steinmetz, established a Consulting Engineer Department and named him Technical Director. His work led to 200 patents.

SUCCESSFUL PERSON

Group Tour of Marconi Wireless Station in 1921 (shown with Albert Einstein)

Many leading scientists and technologists came to visit Steinmetz in Schenectady. They included Edison, Einstein, and Marconi.

Although Steinmetz and Tesla had similar interests in A/C and lightning, I have not seen mention of their knowing each other. Given they were both active in the NYC electric power community, it is hard to imagine. However, they were quite different fellows and may have avoided each other. If Tesla were the model of the idea of a “mad scientist,” Steinmetz appears closer to a “Mister Rogers” personality.

Steinmetz appears to have played a major role in creating an open, informal, and creative atmosphere at GE’s research lab in Schenectady and surrounding areas. He conducted much of his work at home and at his Mohawk River cabin. He also liked to work in his canoe on the river, writing on a board he placed across the hull. From my experience at Bell Labs, I suspect we had Steinmetz to thank for the informal dress codes and relaxed managerial oversight and direction we had there in the 1970s – and which later influenced Silicon Valley, as well.

Because of his inherited malady of dwarfism and hunchback, Steinmetz decided not to marry or have children. As his career advanced, he designed and built a great house on Wendell Avenue in Schenectady, a neighborhood with many GE executives. Steinmetz’s closest assistant, Joseph Hayden, often worked with Steinmetz in the workshop at the house. He occasionally invited Hayden and Hayden’s new wife, Corrine, to dinner. Steinmetz truly wished to have a family life. He proposed that the newlyweds move into his large house. Although non-committal at first, Mrs. Hayden ultimately countered with a conditioned proposal of her own. They would move in if she could run the house as she saw fit. Steinmetz replied, “Of course, my dear,” and the deal was done. The living arrangement worked well, and the Haydens had three children. Steinmetz ultimately adopted his assistant, and Steinmetz became a grandfather of the Hayden children.

His happy arrangement with the Haydens continued until 1923. On a family trip west to the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and Hollywood (including a visit with Douglas Fairbanks). Sadly, the adventure exhausted him, and he died in his sleep from heart failure shortly after returning from the trip.

CONCLUSION

Steinmetz achieved the American Dream. It almost never happened. One immigration official’s routine decision went in a fortunate direction because of the friend with Steinmetz on Ellis Island. He could easily have been sent back to Europe to be imprisoned in Germany or have gone to work for the Bolsheviks (Steinmetz once considered Einstein and Lenin the two greatest minds of his time).

As an immigrant, he made America his adopted home, built a career, made friends at work and home, and contributed to his communities. He was an inspiring figure among the early Wizards of Electricity.

The IEEE named one of its highest honors after him, The IEEE Charles Proteus Steinmetz Award, for major contributions to standardization.

Sources/References

King, Charles Proteus Steinmetz, the Wizard of Schenectady, Smithsonian Magazine, 2011

Norton Leonard, Loki; The Like of Charles Proteus Steinmetz, Classic reprint, 2012

J W Hammond, Charles Proteus Steinmetz: A Biography, 2008 reprint of 1924 biography

Charles Proteus Steinmetz – the giant of alternating current technology, TME, anon., undated

Charles Proteus Steinmetz, Wikipedia, anon., undated

About William F. Hederman

Adjunct Professor of Energy Geopolitics, Maxwell School of Syracuse University and Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC.

Former adviser to U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz, founding Director of U.S. FERC Office of Market Oversight and Investigations, VP of business development and strategic initiatives Columbia Transmission Companies, Executive Director of IEA Gas Technology Centre, Executive Director of Morgan Lewis Energy Resources, Managing Director Deloitte energy regulatory compliance.

BSEE, U of Notre Dame; SMEE, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; MPP, University of California Berkeley.

Recipient of IEEE Award for Distinguished Ethical Practices (2012)